The ashrams and Gurus of ancient India used to be mental

workshops. They taught and molded the minds of people to be clear,

strong, and to act righteously under all possible circumstances.

If all the spiritual teachers started to teach faith in the Self and

stopped teaching faith in a personality, this world would be

heaven. This existence with its infinite mind is at your command.

You need guidance and training to experience and manifest this.

-YOGI BHAJAN

This chapter includes . . .

The ashrams and Gurus of ancient India used to be mental

workshops. They taught and molded the minds of people to be clear,

strong, and to act righteously under all possible circumstances.

If all the spiritual teachers started to teach faith in the Self and

stopped teaching faith in a personality, this world would be

heaven. This existence with its infinite mind is at your command.

You need guidance and training to experience and manifest this.

-YOGI BHAJAN

The Evolution of Yoga through the Historical Epochs

The Six Schools of Yogic Philosophy

38

42

43

43

44

About the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali

Short Glossary of Terms

Patanjali’s Eight Limbs of Yoga Practice

Yamas & niyamas • The eight limbs & the three minds

The eight limbs & the five gross elements

More about the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali

The waves of the mind • Balance of the inner and outer worlds

45

The five stages of mental refinement • The refined mind & Guru Harkrishan

The Evolution of Yoga through the Historical Epochs

TH E SEARCH FOR TRUTH HAS GENERATED MANY SCHOOLS OF

thought and disciplines for experience over thousands of years.

Yoga and the philosophy of consciousness did not spring forth fully

formed and independent of historical and cultural processes. It is

the historian’s job to recast concepts and philosophies so they can

be seen as part of the greater unfolding of historical processes and

the evolution of great ideas. Our job is to appreciate just enough of

that history to help us perceive some order to the evolution of the

schools of philosophy that we will briefly survey. We have a specific

destination: the foundations for yoga and the study of consciousness.

Hence this brief presentation of historical phases is not

intended to satisfy the details necessary for comprehensive history.

It is a conceptual outline to help you recognize and put several key

texts and schools of thought in a temporal order.

Although the process of awakening the kundalini and of transcending

the ego is universal. and can be found in many cultural

traditions. it is in India that the philosophy and the techniques of

the kundalini saw its most complete fruition. This timetable follows

the twists and currents of that great river of knowledge given to us

by the sages and saints of many traditions of the Indian subcontinent.

Remember that all the traditions are linked by a common

quest and by disciplines that guide the student to self-transcendence.

were then reformulated in later cultures at 80,000, 40,000, and

10,000 years ago. and they are being reformulated now.

In the period a few hundred years prior to 1 800 Be, ancient

India was concentrated in the Indus River valley. The civilization

spanned hundreds of miles in the north. northwest, and western

sections of contemporary India and Pakistan. Two great cities have

been excavated: Harappa in the north and Mohenjo-Daro along the

southern end of the Indus River. The people were sophisticated

and had elaborate socio-politico-religious organizations. They carried

on commerce with trade routes stretching from Europe to

China. They even had a system of running water, baths, and a

sewer system that included sit-down toilets in some homes. There

is evidence that the rudiments of yoga were known. and cities contained

as many as 50,000 people by some estimates. The great

cities survived in stable modes for over a thousand years. We know

little of this time. The artifacts and records are sparse. It is clear

that they already had the concept and practice of meditation. They

used symbols for the feminine and masculine powers in the universe

that are still used in modern art and religions.

Although we were not left with specific texts and scriptures.

the motifs of the meditation on Shiva. Shakti, and Vishnu run

through all the later scriptures and techniques.

Prehistoric Epoch (?-1800 scJ

There is evidence that the rudiments of yoga and

meditation are known during this period.

Vedic Epoch (1800 Be -1000 scJ

The Mahabharata is revealed. The realms of the rishis

are recorded in the Vedas. We find the cultural roots of

yoga and the Samkhya philosophy.

We know very little about the civilizations of this early period.

Archaeology has given a few hints. Speculation fills the rest of the

gaps of our knowledge. There are only fragments of later writings

that refer to these early periods. These references are presented in

mythical form. Yogi Bhajan once commented that the oldest

records in the scrolls of Tibet told of civilizations flourishing over

40.000 years ago. He says that even in those times there were

forms of yoga and meditation. The biggest changes in those times

came from the massive shifts in global weather patterns and the

consequent crop and wildlife adaptations. He specifically mentioned

a massive shift in weather about 1 0,000 years ago that

forced migrations. It was these migrations that blended cultures

from different areas and which catalyzed the development of many

of the new cultural forms of spiritual practice. He emphasized that

the early forms of yoga were systematized 100,000 years ago. They

\Vedic Epoch (1800 Be -1000 scJ

The Mahabharata is revealed. The realms of the rishis

are recorded in the Vedas. We find the cultural roots of

yoga and the Samkhya philosophy.

The great migration of the cities of the Indus civil ization by the

Aryans starts the next period. The Aryans were a Sanskrit-speaking

culture that came from the area of the steppes of central

Russia. They had fair skin. light hair and blue eyes. They were

Indo-European nomads (herdsmen) and raiders, and were proud,

aggressive. and warrior-like. They believed in their own superiority,

and they had a great tradition of self-development and yoga.

They had a great variety of weapons. Deep in the core of their

culture. they believed in self-discipline and in the transcendence

of the ego-self.

The Aryans eventually spread into the central areas of India

after establishing in the area of modern day Punjab. This expan-

sian was not peaceful. It was filled with battles, sieges. and grand

conflicts. As they gained wealth and power, they even fought

among their own clans.

The longest war in recorded history is chronicled in the

Mahabharata, a poem of over 1 00,000 stanzas. A playwright once

brought a version of the poem to the stage in New York City. The

play lasted for three full days. It is a record of the battles between

two warring clans: the Pandavas and the Kauravas. The original

version was recorded between 800 and 1 000 sc. It is a storehouse

of myths, symbols, history, philosophy, bel iefs. religion, customs.

and mystical experience. The poem is a source of much lore

about yoga in this period. Over the centuries the Mahabharata

became the central epic of I ndia, and has had many parts added

to it. such as the Bhagavad Gita. And it grew in its role as the

storehouse of cultural knowledge and inspiration.

If you are a serious student, and you want a deep understanding

of the cultural roots of early yoga , then this is required

reading. The earliest version was transmitted orally, and describes

disciplines and sadhanas. The later versions record Samkhya and

yoga philosophies. One of the strongest messages of this epic is

that beyond all the drama, strife. and war, there exist transcendental

states of Being. That liberated state is beyond all opposites:

good and bad. right and wrong, and pain and pleasure. The

personal and internal achievement of that special consciousness

liberates and enlightens the individual.

As the Aryan and Indus cultures merged and influenced each

other, the techniques and experiences of spiritual development

that helped guide the integration of the cultures were recorded in

Sanskrit. in the earliest Vedas (Books of Knowledge): the RigVeda,

the Sarna- Veda, the Yajur-Veda, and the Atharva-Veda. The

Rig-Veda in particular provides stories and hymns about the

adventures and beliefs of the early civilization of the Vedas. These

scriptures came from the Aryans. and they show the influence of

the Indus population in its words and concepts.

The hymns were composed by the great seers or rishis who

had gained a vision from deep contemplation and merger with the

Divine. The hymns were directly spoken and sung from this state

of direct perception. Being in this state of consciousness. they did

not compose the Vedas, but recorded in language the realms they

experienced. These hymns are not intellectual treatises, but the

direct poetic, emotional, and spiritual experiences of the sages.

Brahmanic Epoch (1000 ec • soo ecJ

This is a ritualistic, literal epoch. Yoga and the mystical

precepts for empowering the individual are not promoted.

The priestly class were called Brahmins. They recorded a great

deal of literature about the proper rites, rituals, and behaviors of

the times. They formed a sacrificial and ritualistic class. Worship

and virtue were external. Rather than accept the challenge of

internal development cultivated in the earlier Vedic Epoch, the

Brahmins stabilized their social position through elaborate bodily

rites. Traces of the past were woven through them. but the literal-

thinking minds of fundamentalists were busy at work.

The literature in the Brahmanas and in the Aranyakas, a handbook

for ascetic forest dwellers, does not promote yoga or the precepts

that empower the internal capacities and experiences of the

individual.

Upanishadic Epoch (BOO ec • soo ecJ

The Yoga-Upanishads and the guru-chela relationship

transmit the yogic teachings. King janaka grandly passes on

the traditions of Raj Yoga and Kundalini Yoga.

The reaction to the rigid external ritualism of the Brahmanic

Epoch finally came in the form of the Upan ishads. These ecstatic

writings are full of the technology of transcendence. They are

iconoclastic and inspirational. They internalized all the transformations

of the earlier rituals. They opened the inner ground of

Being as the appropriate place for gradual self-transcendence.

They record the knowledge of many anonymous sages.

The sages of the times who inspired and contributed to the

Upanishads were diverse and unequalled in their sagacity and

vitality. The great King janaka, who was also the transmitter of

the tradition of Raj and Kundalini Yoga, was a grand figure of the

time. Others were ascetics and some were enlightened Brahmins.

Great stories and traditions flow from this epoch.

The word Upanishad literally means to sit near and be meditative.

It reflects the original way the knowledge was transmitted.

It was given from guru to chela. teacher to student, master to

apprentice. It assumed respect and commitment on the part of

the student. There are 1 08 traditionally accepted verses that are

themselves listed in the Muktika-Upanishad. This knowledge is

known as Vedanta and is accepted as revelations or direct transmissions.

Vedanta is known as “The great knowledge which is

complete or which ends the teachings.” Over the centuries, more

than a hundred more verses have been added by various authors.

These newer compositions are respected as both tradition and as

elaboration . There are translations available of all of them and

there are many studies of the content. One group is especially

important: the Yoga-Upanishad. These include a great deal of

instruction on yoga.

All the writings emphasize the discovery and cultivation of an

ultimate ground of Being, that Infinite can be known through

transcendental gnosis. The key insight is that there is an identity

between the Ultimate Truth and the reality of the individual as

truth. The soul and the Universal Being are not different in nature.

This fact is beyond the mind’s capacity for definition and classification.

It requires realization or enlightenment. It must be

known all at once, as a total and complete vision.

from external rituals or sacrifices. The real problem is not the

action of life. but our attachment that keeps us bound to reaction.

I n real liberation, we act free, carefree, and spontaneous

without attachment or fear as motives. When we do not act from

lower motivations, we learn to act from what is cosmically correct

– from dharma. Only then do concepts like love, duty. and

righteousness have any meaning. The writings do not outline systematically

the yoga practices and meditations. Rather. they convey

the spirit and viewpoint that must accompany them.

This became the main scripture for the Va ishnavites. who

worshipped Vishnu. The message of the scriptures is universal ,

however. Vishnu was regarded a s the O n e in a l l a n d the One

beyond all. Awakening was in two main stages: the release of the

attachment and security of time and space, and the absorption

beyond mind into the absolute Being and Love.

Gita Epoch csoo Be – Ao 20oJ

Movement toward systemization of the inner technology. The

Ramayana teaches of Divine Love and self-transcendence;

the Bhagavad Gita the path of dharma, and karma yoga.

Classical Epoch (Ao 200 – Ao soo)

Patanjali reveals his masterpiece of yogic philosophy,

as the long-standing traditions flourish.

During this period, the tradition established in the Mahabharata

flourished and expanded. Many of the streams of thought and the

technologies of yoga were systematized. The six major schools of

philosophy (see Six Schools of Yogic Philosophy this chapter) were

codified and extensively taught. In the later writings of the Sikh

Gurus (the Bhakti Epoch), the “six schools” refer to the philosophies

established in the Classical Epoch. The most important work

during this period was the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali. This is the great

work on yoga and its philosophy that has guided students ever

since it was written. (See this chapter for more on Patanajali’s Sutras.)

Puranic Epoch (Ao soo – Ao 1’169)

Esoteric knowledge becomes widespread, Vedanta

philosophy sets the stage for the grant synthesis of

the next epoch.

The Puranas were composed during this period. They are a huge

collection of mythology, philosophy, and h istory. The great

teacher Shankara wrote about non-dual istic Vedanta philosophy.

His writings propelled many seekers into the use of the psychospiritual

technology of yoga. During the same time the emphasis

on tantrism and the use of the esoteric knowledge of the chakras,

the glands, and the aura expanded. The discipline of sadhana to

elevate consciousness and to aid in the philosophy propounded

by earlier texts became widespread.

It came to be understood that it was possible to produce the

spiritual and physical well-being without rejecting the senses and

without being an ascetic. This emphasis led to an awakening of the

philosophy of Shakti, the feminine cosmic principle of energy.

Kundalini is a Shakti energy that manifests the Divine in the finite

body and mind. This explosion of experimentation and practice

prepared the way for the grand synthesis in the next period.

Bhakti Epoch (AD 11169 – AD 1708)

The grand synthesis creates the householder as the sage.

This is the period where opposites fused. The tradition of asceticism

met the tradition of mystical union. The householder who

must live in the daily world was elevated to the status of the forest-

dwelling sage. The catalyst for this was the meeting of the Sant

tradition (which had respect for the Guru or teacher). the Nath, and

Tantra traditions, (which use yoga and psycho-physical technology),

and the Bhakti tradition, (which emphasized devotion as a

means to know truth beyond the confines of the structure of the

mind).

The greatest result of this confluence of influences was the ten

Sikh Gurus and the creation of the scripture: the Siri Guru Granth

Sahib. Yogi Bhajan has said that the Siri Guru Granth Sahib is the

fifth Veda. It completes and culminates the philosophies of all the

previous times. It also extends them. It is the only scripture that is

treated as a Guru. It is not just history, philosophy, and technology,

it is an active vibratory presence. It was designed as a granth,

a knot that binds the Word into a form in which any person can

interact and be transformed It is a primary source for many

mantras and shabds that are the pinnacle of the power of the

Word as understood by the yogis and saints. The Sikh Gurus

emphasized non-attachment, service, and meditation directly on

the Naam. They broke the cycle of searching for a personal guru

and the cults of personality that often misled seekers. They

embodied the Guru in the scripture and declared it a Siri Guru. a

teacher of teachers. The tenth teacher. Guru Gobind Singh,

declared there would be no more human G urus in that tradition.

The result, the Siri Guru Granth Sahib, is a modern tool and writing

that emphasizes the need to remember the essence of spirituality

and at the same time the need to embody that essence in a distinct

form. It encourages respect for all traditions and people. and

asks each to recognize in others the common essence we share. and

the Creator who creates us all.

Modern Epoch (AD 1708 – Ao Z011J

The romance between East and West begins. A time of

expansion and discovery, great change and possibilities.

The fall of the Mogul Empire brought about by the Sikh resistance

ushered in the changes that opened civilization to Western influence.

The British established rule over India in the latter part of the

eighteenth century. This diminished the devotional ardor of the

Bhakti Epoch. It increased materialism and secularism. It brought

with it industrialization and, later, high technology. At the beginning

of the 1900s there was a wave of missionaries from the East

who brought many of the concepts to the West. The romance

between East and West began in earnest. The Modern Epoch is the

story of discovery and communication between the two hemispheres

of our world. The great traditions have been established.

Now they have been rediscovered, printed, practiced, and disseminated.

In the United States and Europe, meditation and the practices

of Sikhs, Hindus. Muslims. and others are common. The

recent wars in Vietnam, Cambodia. Africa, Thailand, and the fall

of the old hierarchies in Eastern Europe have led to a great migration

of people across the old cultural barriers. With the rise of

japan as a great economic power and the people fleeing China and

Hong Kong, the oriental cultures have come face to face with the

West. Buddhism, Shintoism, and Taoism have touched the

Western heart and are being assimilated. The Modern Epoch is one

of expansion and discovery. We near the end of that time and prepare

to enter the next epoch. These years will be filled with change,

chaos, and possibilities. The roles of the individual and institutions

will need to find a new balance. Many institutions preserved themselves

through ignorance and fear. The barriers to knowledge have

been attacked by the people and technology of the modern information

era.

Aquarian Epoch (Ao 2011 – ?J

A period based on experience, commitment, and

universality, ushering in a new level of consciousness

and civilization.

The Six Schools of Yogic Philosophy

The key terms for the Aquarian Epoch are globalization,

universality, and the dignity of the human being. No religion

will survive in less than a global context. The historical and

tribal- based traditions of the many world cultures will come

face to face. The need is a comm itment to establish authentic

transformative experience in each i n dividual .

Consciousness and its many levels will be the theme i n this

epoch.

Traditions that rely on fear and ignorance will fall to the

side. During this transition, there will be a polarization and

some chaos as old institutions fight the final battle. Then

there will be neither East nor West. There will be developed

and undeveloped consciousness. We will judge philosophy

and spirituality by the degree of awakening and embodiment

an individual attains, rather than by their association with a

specific group.

The end of the Aquarian Epoch is in dispute from different

sources. By astrological, rather than historical measure, it

should last about 2,000 years. Yogi Bhajan has said that if all

goes well in the transition, the realm of global philosophy,

pluralism, sprituality, and the ethics of Khalsa (the pure ones)

will extend a full 1 1 ,000 years before they pass on. This length

of time will be historically unique-it will be the first time that

the entire globe will be united. It can be a period of stability,

and expansion can occur in the depth of our hearts and in the

reaches of space. Inner and outer space will complement each

other and lead to a vast spirituality and a philosophy that is

based on experience, commitment, and universality.

Each of you who studies these ancient techniques and

puts them into practice in your life is a pioneer of the New

Age. You a re on the historical crest of hope and development

that will usher in a new level of consciousness and civilization.

The changes will happen very quickly. Each of your

efforts to study and to teach Kundalini Yoga gives birth to

the Aquarian Epoch.

The six principal orthodox schools recognized as representing

points of view within the context of Vedic heritage are:

Purva-Mimamsa expounds in detail the art and science of

moral and righteous action by following the proscriptions of

vedic ritualism. It was focused on the concept of dharma.

Purva-Mimamsa emphasizes individual responsibil ity for one’s

actions and that we have the free will to create a quality of life.

We find no instruction in yoga in this school. Nor does this

school presume one God.

Vedanta (Uttara Mimamsa) In this school we find an

emphasis on the internal experience of ritual, as well as the

nature of meditation and the mystic scriptures of the

Upanishads, including the Bhagavad Gita. Here we find the

integration of the concept of right action within the Oneness of

creation, and the nature of transcendental reality.

Samkhya has many schools which are concerned with the

evolution of existence, and the nature of being. The elements of

Samkhya philosophy are woven through classical yogic philosophy.

But samkhya stresses the use of mental discrimination and

analysis to perceive reality, rather than meditative experience.

Yoga This school was identified throughout Patanjali’s sutras.

It expounded practical techniques of meditation and self-control

to attain the perception of self and reality. With this school, we

find movement into the more experiential.

Vaisheshika approached liberation by understanding all of

existence in terms of six primary categories.

Nyaya (literally means 11 rule. 11 ) Emphasis in this school was

on rules, logic and rhetoric.

About the Yoga Sutras of Pataltiali

I N THE VISION OF PATANJALI, and most Eastern and esoteric

traditions , knowledge serves the function of awakening and even

redeeming. It is through clarity, intuition, and understanding the

timeless nature of the Self, that we can transcend suffering and

stop the unconscious actions that create problems.

Patatrjatrs Sutras . . .

consist of 195 thought-laden aphorisms. Sutra means

“thread.”

remain even today, the definitive work on yoga.

are an overview of the goals, philosophy, and structure of a

yoga and meditation discipline.

state that the process of yoga is focused on the need to

control the modifications or waves of the mind.

describe the Eight Limbs of Yoga essential for yoga practice.

merge the two schools of Yoga and Samkhya. Yoga

recognizes our individual consciousness as one with the

Universal Consciousness, Samkhya explains how our

unlimited consciousness manifests into the realm of the

physical world.

The Yoga Sutra itself consists of 1 95 aphorisms presented in four

steps or chapters.

SAMADHI-PADA

Absorption and Higher States of Awareness

II SADHANA-PADA

Discipline and Practices

Ill VIBHUTI-PADA

Powers and Capabilities of the Possible Human

IV KAIVALYA-PADA

The Nature of Liberation

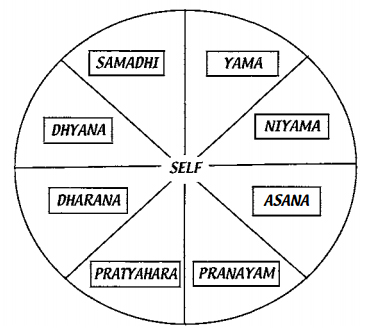

Patalfjalf’s Eight Limbs of Yoga Practice

Ashtanga (8-limbed) Yoga

One of the deep truths captured by the eight limbs is the

need to develop the entire spectrum of body and mind as

a whole system. Kundalini Yoga includes all eight limbs

in each sadhana or complete set.

PATANJAU IDENTIFIED EIGHT I NTERRELATED ASPECTS OF YOGA

practice some time betwen 200 and 600 AD. The eight limbs are

equally essential to steady progress in refining the m ind and discriminating

the real from the illusory. They are called ” limbs” or

” parts” rather than steps to emphasize their integrated nature.

The limbs grow a little in relation to each other, allowing the

coordinated use of all the limbs.

SAMADHI

DHYANA

DHARANA

PRATYHAR

PRANAYAM

AS ANA

NIYAMA

YAMA

Awakening and absorption in spirit

Deep meditation

One-pointed concentration

Synchronization of senses and thoughts

Control of prana (life force)

Postures for health and meditation

Five disciplines [see below]

Five restraints [see below]

The list above places the eight limbs in a ladder-like manner, missing

the dynamic aspects of the limbs, but emphasizes the natu re of

the practices from the most gross and accessible (ethical behaviors)

to the most rarified and intangible (spiritual or mystic merger).

In the West, most popularizations of the techniques tend to

emphasize one end or the other of the ladder. Either the body is

cultivated without chanting and meditation, or the mind is cultivated

through meditation, without building physical vitality

through exercise. Both lead to imbalances, physically and emotionally.

One of the deep truths captu red by the eight limbs is the

need to develop the entire spectrum of body and m ind as a whole

system. Kundalini Yoga includes all of the eight limbs in each sadhana

or complete exercise set.

Yamas and niyamas

At the base of the eighted-limbed path are the yamas and

niyamas. Yama is choosing to practice moral restraint in external

interactions, and niyama is observing daily practices designed to

clarify the internal relationship to the Self.

YAMAS

Ahimsa (non-hurting). Compassion, patience, love for others,

self-love, worthiness, and understanding,

Satya (truthfulness). Honesty, forgiveness, non-judgment, owning

feelings, loving communication, letting go of masks.

Asteya (non-stealing). Right use of resources, letting go of jealousy,

cultivating sense of self-sufficiency and completeness.

Brahmacharya (sensory control). Channelling emotions, moderation.

Aparigraha (non-possessiveness). Fulfilling needs rather than wants.

NIYAMAS

Shaucha (purity). Evenness of mind, thought, speech. Purity of body.

Santosha (contentment). Gratitude, acceptance, calmness with success

or failure.

Tapas (purification, zeal). Determination, willingness for practices.

Svadhyaya (study). Reflection, meditation, expanding knowledge.

lshvara pranidhana (devotion, surrender). Faith, dedication.

The eight limbs and the three minds

The negative mind is mastered with YAMAS and NIYAMAS.

The positive mind is mastered with ASANAS and PRANAYAM.

The neutral mind is mastered with PRATYAHAR, DHARANA,

DHYANA, and SAMADHI.

The Eight limbs and the five gross elements

Earth: habits-confronted by YAMAS.

Water: emotional impulse-guided by NIYAMAS.

Fire: energy and the urge to do-tended by ASANA.

Air: sensitivity and feelings -directed by PRANAYAM.

Ether: the creative inner space -navigated with

PRATYHAR, DHARANA, DHYANA, and SAMADHI.

More about the Yoga Sutras of Patalfjali

PATANJALI’S SUTRAS, A SHORT CODIFICATION OF THE PRACTICE

of yoga, came out of the classical period of yoga philosophy and

history (200-800 AD).

The Patanjali Sutras are an overview of the goals, philosophy,

and structure of a yoga and meditation discipline. They provide a

sketch of the effort needed and the progress to be expected in a

yoga discipline. They are a map of the process of awakening and

realizing the possible human that is in each of us. As ancient as

they are, they are still an excellent foundation for any serious student

of Kundalini Yoga.

The sutras were written, as many are, in short thought-laden

sentences, assumed to be used under the direction of a master. Its

brevity is a problem and a blessing. A great deal is assumed, making

its use difficult. However, that allows for a wide range of adaptation

to the Teachers who use the sutras. Several teachers have

written commentaries on the sutras to bridge their particular purposes

and audiences. That further emphasizes the importance of a

relationship to a Teacher and teaching community as part of the

process of spiritual practice and growth. There are other texts that

l ist many specific tech niques.

Most yogis preferred direct cultivation of personal experience

and capacity rather than the intellectual enterprise of systematizing,

classifying and analyzing. Substantial commentaries that came from

intellectual efforts of great scope were rare. Patanjali Sutras represent

the efforts of a yogic adept to attempt to trace the central thread of

process across the many schools of practice that existed in the early

Classical Epoch (which corresponded to the Christian era) in India.

They were so well conceived and written, that they rapidly became

the central authoritative text in the yoga tradition. Patanjali’s contribution

seems to be mostly that of a systematizer rather than an originator.

The true beginning of yoga is always attributed to “the womb

of Being” or the Creator. The Sutras are the culmination of the historical

development of yoga up to that point.

In Hindu stories, Patanjali is said to be an incarnation of

Ananta-the thousand-headed ruler of the serpent race. This icon

has the job of guarding the deep treasures of the Earth. The treasure

is the knowledge given by yoga to awaken the possible human;

the ability to manifest the Heavens in the Earth, and the ability to

embody the divine aspects of the self in the profane circumstances

of the normal life. Patanjali’s name came from his desire to teach

and enlighten those of Earth. He fell (pat) from the Heavens and

landed in the palm (anjali) of a saintly woman, his mother,

Gonika. The reverence given to his efforts and its impact on the

tradition of the times is clearly evident.

The Yoga sutras themselves consists of 195 aphorisms presented

in fou r steps or chapters.

SAMADH I-PADA. Absorption and higher states of awareness.

II SADHANA-PADA. Discipline and Practices.

Ill VIBHUTI-PADA. Powers & capabilities of the possible human.

IV KAIVAlYA-PADA. The nature of liberation.

Many scholars argue about the proper order of the aphorisms

in the original unedited text. But taken all together the current version

seems authentic and reasonably complete.

The form of yoga that comes from this compendium is usually

called Classical Yoga. There are some differences with this and

Kundalini Yoga, mostly because Classical Yoga was intended for

monks, people who withdrew from the world for spiritual practice.

Kundalini Yoga was designed for people in the world.

The waves of the mind

The Classical Yoga system Patanjali described was meant to

include and unify the precepts developed in Samkhya philosophy

and in Vedanta. The process of yoga is focused on the need to

control the modifications or waves of the mind. (See Mind &

Meditation chapter.) The mind is considered the link between body

and spirit or consciousness. It is the habits of the mind that bind

us to attachments and duality and, in turn, suffering. It is also the

habit of mind that leads to non-attachment and to the practice of

merger with what is real. The mind is a sophisticated tool that can

give us liberation and the transcendence of conditional living, or it

can give us confusion, ignorance, and bondage.

The mind and body are one emanation of the primal nature:

Prakirti. A fundamental property of this nature is constant evolution

and transformation. The result of this transformation is the

creation of a multilevel gradation of nature from the most subtle

and unmanifest aspects to the most differentiated and gross realm

of the five senses. Body and m ind-the “psyche”- are considered

to be gradations of the same substance produced through three

eternal forces-the gunas. (See Yogic Philosophy chapter for more on

gunas.)

The mind is divided into functional aspects:

manas-the lower mind of senses and reactions;

ahangkar-the ego;

buddhi-discriminating m ind or mind stuff, which includes

memories, subconscious realms, intellect; and

chitta-all other fluctuating waves of mind.

The central task of the yogi is to calm these mental functions

so that a clear perception of what is real and what is false can arise.

PATANJALrS SUTRAS

This is the central goal. Patanjali attributes the universal suffering

witnessed throughout life not to an angry God, nor to any form of

original sin or unworth iness, but to ignorance, the lack of the ability

to properly discern the real from the unreal, the eternal from

the transitory, the essential from the peripheral, and the Self from

the world of experience-maya. Because we are wrapped in layers

of mental and emotional habits that cloud our perception, we make

choices that are against the Self. We initiate sequences of action

with long term pain as their consequence. The moment we do that

we are asleep. We are viewing the moment of choice through the

blinders of ego. If we can awaken, we can discern the reality of the

choice and stay in alignment with what is. Action in line with the

Infinite Self is called dharma. You act in the right way at the right

time. Dharmic action takes you beyond pleasure and pain to ecstasy,

beyond like and hate to love, and beyond want and need to

duty, commitment, and identity.

In the vision of Patanjali. and most Eastern and esoteric traditions,

knowledge serves the function of awakening and even

redeeming. It is through clarity, intuition and special forms of

knowing when the m ind is refined that we can transcend suffering

and stop the unconscious actions that create problems.

The Samkhya and Vedanta traditions were woven together by

Patanjali into the eight-fold path of yoga. Vedanta and yoga emphasize

the use of meditation and other exercises as part of training the

mind. He bridged the few critical differences in a manner that gave

greater accessibility to the yoga approach in gaining knowledge of

the Self. Both traditions recognize the importance of self-knowledge.

But classical Samkhya emphasizes pure metaphysical knowledge.

The methodology of meditation supports and complements

the power of gnosis or sacred knowledge. Real knowledge makes us

aware that we are more than how we usually perceive ourselves. As

we recognize the transitory nature of all experience we gain nonattachment.

Through the practice of yoga discipline-sadhana-we calm the

mind, sharpen its function, and gain discernment to recognize the

real. to hear the inner Word, to follow the impulse of the heartthe

path of dharma.

Balance of the inner fr outer worlds

Kundalini Yoga and humanology concur with Patanjali’s integration.

One departure point is a tendency in Classical Yoga to reject the

world and nature as profane or soiled. Some students take this as a

validation of asceticism. Kundalini Yoga views nature as the sacred

play of the eternal. It is a creation of God the artist. It is a final devolution

of the spirit to its densest form. But the physical body shares

the same elements and qualities that form all of creation. The body

should be viewed as a temple full of treasures. It has the capacity to

influence the mind through breathing and glandular secretion.

Careful cultivation of the body aids the project of gaining inner

knowledge. Neglect and degradation of the body confuses the mind

and creates ill health. In Kundalini Yoga there is a constant balance

of health, happiness. and holiness. It is designed to give the practitioner

awareness and balance in both the inner and outer worlds.

Patanjali emphasizes the need to approach this task with an

equal emphasis on practices and attitudes. The practices include

the eight l imbs of yoga, mental training, concentration, and breathing.

If those are practiced alone, the aspirant is subject to great

spiritual ego from accomplishments and special feats of mind and

body. The attitudes include the yamas and niyamas discussed

below. and the primary attitude of non-attachment to the many

aspects of maya. If only non-attachment is practiced, the aspirant

releases a great deal of psychic energy with no place for it to transform

and be expressed. The result is unexpected neurotic patterns,

the sudden emergence of the shadow aspects of the personality or

other psychosomatic manifestations.

With both regular practice and constant attitudes the path is

clear and without problems.

The five stages of mental refinement

The qual ity of mental and emotional experience changes as the

aspirant guides the mind through the eight limbs of yoga practice.

Patanjali describes five stages of mental refinement. The descriptions

reflect the general principle that all emanations of Prakirti are

composed of some combination of the three gunas: tamas (heavy,

confusion, lack of clarity); rajas (activity, energy); sattva (balance,

subtlety, clarity). The qualities of mind reflect different degrees of

activity and combinations of the three gunas.

The Five Stages of Refinement, their description and the influence

of the corresponding gunas follow:

I . NIRUDHA. Sattva is fully expressed. Total calm. The transcendent

perception of the soul, consciousness or Purusha is now possible.

It is “well-controlled,” can distinguishg false from Real, and see

the nature of the Self reflected throughout the mirror of Prakirti.

2. EKAGRA. Sattva rules. This creates tranquility and calmness.

clear perception about the nature of things. The mind is able to

manifest its intentions.

3. VIKSI PTA. Rajas dom inates, so the mind is fast, flighty,

almost manic. It never rests on one thing, nor commits. Often seeks

stimulation and information, but doesn’t analyze.

4. MUDHA. Predominance of tamas assures laziness, confusion,

sluggishness, ignorance, and even vice. It is a state of dull confusion

or stupidity.

5. KSI PTA. Rajas gives the mind a lot of energy. This combined

with tamas loses discrimination. The mind is distrubed, irritated,

erratic, distracted. Attention is often focused on the wrong things.

The first three states are the normal qualities of the mind that a

novice discovers when beginning to meditate. Gradually the first two

conditions are created and slowly developed into steady states. In

this condition the many dimensions of capability and extraordinary

sensitivity unfold. This process of refinement is discussed by

Patanjali both as an increasing unification of consciousness and as

an incremental purification of mind. Purification removes the disturbing

elements of the mind and body. Unification increases the

scope of awareness and the integration across many parts of the

mind.

As the mind is refined, judgment also improves. The aspirant

makes consistent decisions that lead to happiness and growth. The

final result is not a psychological state. It is a condition of the mind

and a relationship of body, mind and spirit that frees the soul to

create and express without hindrance.

This appreciation of refinement disposes the yogi to pay as

much attention to the process and quality of thought and emotion

as to the content of those thoughts. It is like the old adage: ” You

can pile scriptures sky high on the back of a donkey, and it’s still

just an ass.” The mere recitation of written or book knowledge does

not mean the mind has been refined enough to be able to understand,

act on, and embody the things being referred to in the

abstract. The ability to manifest from the abstract to the concrete,

from the general to the specific, and from the subtle to the gross is

the result of extensive psychoenergetic development and psychological

integration. The fact that we can represent things abstractly to

ourselves is part of our creativity and part of our ability to delude

ou rselves.

The mind’s capacity to represent things gives us both creativity

and self-delusion. That is one reason that all spiritual and developmental

paths require a teacher, Guru, or guide to test the student.

The job of the teacher is to be sure the knowledge is learned

in the heart, in the present, and eternally. Our tendency to appear

right or better for others , combined with ambitions and insecurities

often produce false victories and false failures. The teacher keeps

the student going past the limitations of the beliefs and experiences,

especially the successes. of the student.

For an in-depth study and commentary of the sutras, see How to Know

God: The Yoga Aphorisms of Patanjali, by Swami Prabhavanada and

Christopher Isherwood. Vedanta Press, 1953.

पौराणिक कथाओं, प्रेरक क्षण, मंदिरों, धर्मों, फिल्मों, हस्तियों के बारे में दिलचस्प जानकारी, हजारों गाने, भजन, आरती के बोल हैं Your wish may come true today…

पौराणिक कथाओं, प्रेरक क्षण, मंदिरों, धर्मों, फिल्मों, हस्तियों के बारे में दिलचस्प जानकारी, हजारों गाने, भजन, आरती के बोल हैं Your wish may come true today…